The Isaiah Berlin Lectures

The Isaiah Berlin Visiting Professorship brings leading scholars in the history of philosophy or history of ideas to Oxford for a term in which they give a series of lectures. Details of lecture series in the history of philosophy are presented on this page.

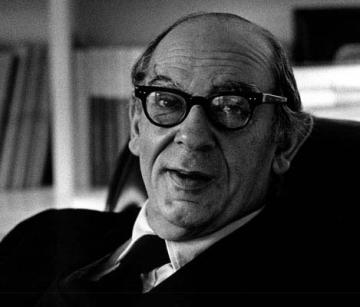

These lecture series were established in 2004, and mark the great British philosopher, and founding president of Wolfson College, Sir Isaiah Berlin (pictured, right). The lectures on this page are usually organised by the Faculty of Philosophy, but Berlin’s legacy is further commemorated with an annual lecture held at Wolfson College, which also houses the Isaiah Berlin Virtual Library. Those interested in Berlin's legacy may wish to look at the Isaiah Berlin Online website. For any queries about the annual lecture or Wolfson’s support of Berlin’s legacy, you can email: berlin@wolfson.ox.ac.uk.

Michaelmas Term 2024

Photo credit: Sameer A. Khan/Fotobuddy

Professor Melissa Lane (Princeton University)

'Lycurgus to Moses: Thinking through Lawgivers in Legal and Political Philosophy'

Abstract: Why and how have lawgivers figured in legal and political philosophy, both in history and in theory? Are lawgivers necessary for the emergence of law as a social practice, and if not, what roles have they played in the shaping and promulgating of bodies of law for particular societies? How have lawgivers deployed different means of legal transmission, such as orality and writing, been deployed to shape civic culture and values? What does it mean to debate legal questions in light of the purported intentions of a lawgiver? Why have so many political theorists and legal philosophers felt the need to appeal theoretically to the figure of a lawgiver or legislator in their own work? And is legislation in fact the core political activity? These questions can be asked in multiple registers, both historical and theoretical, and across manifold historical contexts. These lectures weave together the roles of lawgivers in archaic and early classical Greece, including both historical sources and the ways in which Greek authors themselves constructed those figures; they also extend into the early Christian era, during which Moses was explicitly compared by Jewish authors, writing in Greek, to the panoply of Greek lawgivers such as the Spartan Lycurgus (the most iconic, though not the earliest, Greek lawgiver). That arc—from Lycurgus in seventh-century Sparta, to Moses as conceived by these authors in the early Common Era—would feed into a long trajectory of invocations of lawgivers made by authors such as Rousseau and Nietzsche. Putting the history of ancient Greek lawgivers (part of a larger legacy of Greek law) in dialogue with its reception in the history of political thought, and with questions in legal theory and philosophy about promulgation, purpose, and interpretation, these six Isaiah Berlin Lectures call attention to manifold ways in which the figure of the lawgiver inflects both the history and the practice of legal and political philosophy.

Lectures

29 Oct: Genealogies of law and lawgivers from Zaleucus to Hart

Why and how have lawgivers figured in legal and political philosophy, both in history and in theory? The question can be asked of the contemporary legal philosopher Herbert Hart, who discussed a putative sovereign lawgiver dubbed ‘Rex’ as part of his critique of John Austin, before introducing his own genealogical reconstruction of the origin of law. Yet it can also be asked of political theorists such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who denied that the ‘great Legislator’ necessary for the institution of a social contract should be sovereign at all. And it can be asked of authors who wrote in ancient Greek, whose ideas about the nature of law and politics were formulated both in practice and in philosophical theorising through appeal to such figures: from classical accounts of Zaleucus (believed to be the first Greek lawgiver) and Lycurgus (the most influential), to the discussion of Moses in comparison to Greek lawgivers by post-classical authors Philo and Josephus (both writing in Greek). I argue that no more than in Hart’s genealogy, or Philip Pettit’s recent reworking thereof, did the ancient Greeks generally understand lawgivers to have been necessary for law to come into being as a social institution. Rather, Greek lawgivers can be construed as having served as embodied versions of Hart’s ‘rules of recognition’, making identifiable the relevance and applicability of a particular set of laws to a particular community. Unlike Hart, however, the Greek lawgivers were also construed as having centered the moral purpose of law: each singular lawgiver was attributed with a particular telos or purpose unifying the body of laws that they promulgated. The next lecture explores the role of the telos of the lawgiver.

5 Nov: Functions of lawgivers from Solon to Fuller

While ancient Greek lawgivers can be construed as embodied versions of Hart’s ‘rules of recognition’, their role went beyond that of identifying the authoritativeness of a set of laws. The most intuitive way to construe a set of laws as having an ethical purpose or telos is to construe them as having been composed by a lawgiver (as opposed to simply evolving piecemeal over time). This helps to explain the appeal to the lawgiver in the legal philosophy of Lon Fuller, who championed a purposive interpretation of the nature of law. It also helps to explain the appeal to the lawgiver Solon by his Athenian contemporaries and their descendants. I argue that Solon as a lawgiver, a role which he coupled with that of poet, embodied both the function of identifying the laws of the Athenian community and simultaneously their ethical telos. To be an Athenian was to accept the laws of Solon—yet the questions of ratification and legitimacy look different when conceived through the ancient Greek lawgiver lens, in which the ‘laws of Solon’ did not count as such in virtue of having been passed by the assembly or any other collective lawmaking institution.

12 Nov: The lawgiver's point of view in Plato and Aristotle

I argued in the preceding lecture that the making of new laws was not the key political function for ancient Athenians or their peers elsewhere in Greece—since a good polity would be shaped by the laws given by a great lawgiver, which could be modified by later citizens but should for civic flourishing be broadly preserved. While citizens in classical Athens often spoke about the role of the lawgiver, they did so primarily as interpreters: thinking their way into what the lawgiver intended, and seeking to act so as to sustain that telos. Their interpretative stance—which resonates in significant ways with that of modern legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin—in turn became central to the political philosophy of both Plato and Aristotle. Plato writes from the standpoint of what I have elsewhere called ‘discursive legislation’ from an early point in both the Republic and the Laws, while Aristotle frames his inquiry in in both the Nicomachean Ethics and the Politics in terms of what the good lawgiver would need to know and do. In this lecture, I evaluate the significance and distinctiveness of philosophising about politics from the standpoint of the lawgiver in these two ancient Greek philosophers. I argue that the figure of the lawgiver, possessed of a techne of lawgiving, helped both Plato and Aristotle to navigate the nomos-phusis debate of their predecessors (as to whether laws are artificial or natural), and likewise, can help navigate later debates between positivism and natural law.

19 Nov: Written laws? Ethical education in Plutarch's Lycurgus and related debates

While the previous lecture explored the framing of two major Platonic dialogues as projects of discursive legislation, this lecture turns to Plato’s meditations on the relationship between writing and law and their afterlife. I focus especially on the figure of the legendary Spartan lawgiver Lycurgus, who would be framed in a biography composed by Plutarch (a so-called middle Platonist) as having prohibited the writing down of his laws. Plutarch was intervening in an ongoing debate, articulated by Plato but also revolving around the evaluation of Lycurgan Sparta, about how the telos of a constitution could be best inculcated in its citizens: whether by using written laws, or by relying on unwritten laws that are customary and engrained through practices. Issues of flexibility, precision, memory and habituation were all at stake. Indeed, this debate was in antiquity framed not only in Platonic terms, but also in Hebraic ones, as I explain by reading Plutarch against the backdrop of Alexandrian Jewish texts. I draw implications for debates about how best to inculcate ethical values in education in subsequent generations, including our own.

26 Nov: Moses and Greek lawgivers in Philo, Josephus and Rousseau

Emerging from the Greek-speaking Jewish community discussed in the previous lecture, Philo of Alexandria would argue (in Greek) that the act of writing was key to the extraordinary success of ethical habituation in Jewish law and thereby in Jewish history, both in terms of externally written law and the law that could on its basis be inscribed within the soul. The Jewish general Josephus, who would move from Jerusalem to Rome in the course of an eventful life navigating complex political tensions, would later similarly argue (also in Greek) that the Jewish people were superlatively successful in their mode of studying and internalising their laws. In contrast to those early rabbis who insisted that Moses was merely the transmitter of divinely ordained laws, these authors treated Moses as a lawgiver, but one who excelled his pagan Greek predecessors, in part, according to Philo, by combining the roles of priest, prophet, king and lawgiver. These ancient comparisons of Moses to Greek lawgivers can shed light on early modern invocations of all of these figures, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s appeal to Moses, Lycurgus and others in formulating the theoretical role of his ‘great Legislator’. I argue that Rousseau’s invocation of this figure was in certain respects deeply faithful to ancient Greek understandings of their own lawgivers: figures who drew on their wisdom to shape bodies of law that succeeded in impressing a civic identity on a given polity. While Rousseau’s invocation of a general will as necessary to make those laws legitimate drew on conceptual sources alien to the Greeks, I explore its similarities and differences to the acceptance of and identification with the laws by ancient Greek citizens that I discussed in earlier lectures.

3 Dec: Are we all legislators now? Athens to Nietzsche

Calls to (re-)enact the role of the great lawgivers in the centuries between antiquity and today have been recurrent in many contexts, which this closing lecture can do no more than selectively survey. I begin by considering the Athenians’ institution of a new procedure for lawmaking in 403 BCE, which established a large body of ordinary citizens called nomothetai, inheriting the title of nomothetēs that had been accorded to Solon and Draco, but inverting their function: instead of framing the laws themselves as those individuals had done, the collective body instead vote on new laws proposed by others. Some eighty years later, Athens would witness Demetrius of Phalerum asserting himself as a new lawgiver, while in the meantime, both Plato and Aristotle had framed their philosophical reflections on politics in terms of the standpoint of the legislator, as argued in an earlier lecture. The effort to act as a lawgiver either in theory or in practice would be iterated throughout later centuries, in calls such as Friedrich Nietzsche’s for the emergence of ‘legislators of the future’, and in Richard Tuck’s observation that, as modern democratic theorists and citizens, ‘we are all legislators now’. By contrast, the very success attributed in antiquity to the great Greek lawgivers served to make subsequent lawgiving a far less salient part of ongoing political life than most accounts of ancient Greek politics have assumed. I close this series by reflecting on this paradox and its implications.

Professor Béatrice Longuenesse (New York University)

'Kant and Freud on the Mind'

Professor Béatrice Longuenesse delivered the Isaiah Berlin Lectures in Michaelmas Term 2022. Professor Longuenesse is Silver Professor, Professor of Philosophy Emerita (NYU) and a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Her lectures took place on Weds 9th, Weds 16th, Thurs 17th and Thurs 24th November 2022.

Abstract

It may seem surprising to compare the eighteenth-century Enlightenment philosopher, Immanuel Kant, with Sigmund Freud, the founder of a discipline which explores the darkest, most irrational aspects of our minds. But as a matter of historical fact, Freud is the direct heir of a nineteenth century school of naturalistic philosophy of mind which called itself “physiological Kantianism.” This makes it less surprising that the structures of mental life we find in what Freud called his “metapsychology” should be, in important respects, comparable to those we find in Kant’s transcendental philosophy.

The goal of these lectures is not to repeat arguments I have developed elsewhere concerning the structural similarities between Kant’s and Freud’s respective views of the mind. Rather, the goal is to put those arguments to the test by focusing on specific questions such as the following. What is the role and import of unity and disunity in our mental life, according to Kant’s and Freud’s respective views of the mind? To what extent and in what sense does Kant acknowledge the existence of mental representations and mental activities of which we are not conscious? To what extent is Freud justified in claiming radical novelty for his concept of “the unconscious”? What are the consequences of Kant’s and Freud’s respective accounts of the mind for our normative and moral attitudes?

ORLO reading list for the lectures

9 Nov: Conflicting Logics of the Mind

In previous work, I have claimed that Sigmund Freud’s and Immanuel Kant’s respective views of the structures of human mental life in cognition and in morality present striking similarities. The goal of this lecture is to respond to objections to my admittedly surprising claims.

The central objection under consideration concerns the contrast between, on the one hand, Kant’s view of what he calls the “unity of consciousness,” which he takes to be fundamental to our mental life; and, on the other, Freud’s conception of what he takes to be the insuperably conflicted nature of our mental life. Another objection is that Freud’s investigation of the mind is psychological and clinical, whereas Kant’s is epistemological and (in Kant’s own terms, to be explained) “transcendental.” I acknowledge the force of the objections and I offer responses to them. I conclude this lecture by noting that one important condition for properly adjudicating the differences between Freud’s view of the mind and Kant’s is to clarify their respective views of “conscious” vs. “unconscious” representations. This will be the topic of the next two lectures.

Suggested Readings for Lecture 1:

Freud, Sigmund. The Ego and the Id, Sections 1 & 2. In The Standard Edition of the Psychological works of Sigmund Freud, vol.19, p.12–27.

Longuenesse, Béatrice. I, Me, Mine. Back to Kant and Back Again, Chapter 7.

Lear, Jonathan. “A Freudian Naturalization of Kantian Philosophy,” sections 1, 2, 3, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. XVIII no 3, May 2019, p.748– 55.

Longuenesse, Béatrice: “Response to Jonathan Lear,” Op.cit., sections 4.1 & 4.2, pp.774–78.

16 Nov: Kant on Consciousness and its Limits

I argue that we can find in Kant a distinction that is close to Ned Block’s distinction between “phenomenal” and “access” consciousness, namely, between there being something it’s like for the subject of a mental state to be in that state (phenomenal consciousness), on the one hand; and the state’s content being available for judging, reasoning, and guiding action (access consciousness), on the other. I argue that heeding that distinction allows us to understand the very different ways in which cognitive states (for Kant: sensations, intuitions or concepts) can be, for Kant, “with” or “without” consciousness.

Having clarified those distinctions, I argue that for Kant, more fundamental than state consciousness is what we would call “creature consciousness”: consciousness, by the subject of a state, of being, itself, in that state. However, Kant surprisingly claims that this type of consciousness can itself be something of which we are not conscious. I explain how this apparent contradiction may be resolved in light of the distinctions introduced earlier in connection with mental states: the distinction between “phenomenal” and “access” consciousness.The upshot is that Kant offers rich and subtle insights into the conscious and unconscious aspects of our mental life. Freud was wrong, then, to claim that he was the first to recognize that what is mental is not necessarily conscious. And yet, Freud was right to take his own discovery of what he called “the unconscious” to be radically novel. This is the argument of the next lecture.

Suggested readings for Lecture 2

Kant:

- Critique of Pure Reason, the “Stufenleiter”, A320/B376–A320/B377. On the activity of imagination as one of which we are “seldom even conscious”: A78/B103. On empirical consciousness and apperception: A117n.

- Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View, §§ 5 & 6, AA 7, 135–40.

- The Jäsche Logic, in Lectures on Logic, p.567–69. AA9: 62–65.

(All English texts are from the Guyer/Wood Cambridge Edition of the Complete Works of Immanuel Kant, available online)

Block: “On a confusion about a function of consciousness.” In Behavioral and Brain Sciences (1995), 18: 227–87.

17 Nov: Freud’s Concept of the Unconscious

Freud was far from the first to defend the view that many of our mental states and mental activities are not conscious. This is a view Freud shares with quite a few early modern and modern philosophers, including Kant.

Nevertheless, Freud is right to claim that his concept of “the unconscious” is radically new. The goal of this Lecture 3 is to clarify what makes it novel. It is also to answer the question: If Freud’s concept of what, in our mental life, is unconscious, puts him at a distance from Kant’s, how is acknowledging this distance compatible with claiming that Freud’s and Kant’s respective views of the structure of mental life are similar?

What Freud means by “consciousness,” as a property of mental states, is what we call phenomenal consciousness: the qualitative presence, for the subject of a mental state, of that mental state and its content. A representation that is not conscious is, in the broadest sense, a representation that lacks this phenomenal character. But Freud’s originality lies in his investigation of a narrower subset of representations that lack the quality of being conscious, namely, those that lack that quality because, according to Freud, they are repressed. I investigate Freud’s concept of repression and argue that it must be understood in light of its relation to three fundamental aspects of mental life: memory, biological/psychological drives (for instance, hunger, aggression or lust), and affective states (pleasure or pain). I argue that what is fundamental in Freud’s concept of “the unconscious” is not so much whether representational states have or lack the quality of phenomenal consciousness. Rather it is how, unbeknownst to us, drives and affects interfere with the rational organization of our memories and their function in cognition and volition.

That interference is especially salient when, after considering (in lecture 1), the parallel between Freud’s “ego” and Kant’s unity of apperception, we consider another important aspect of the parallel between Kant’s and Freud’s respective views of the mind: Kant’s “categorical imperative” of morality, on the one hand; and Freud’s “super-ego,” on the other. Or what Bernard Williams called the “morality system.” This is the topic for the next lecture.

Suggested readings for Lecture 3:

Freud, “The Unconscious.” The Standard Edition of the Psychological Works of Sigmund

Freud, vol.14, p.166–204.

Freud, “Remembering, Repeating, and Working Through.” Ibid., vol.12,145–56.

24 Nov: The “Morality System”

In Lecture 1, I argued that the mental structure Freud called “ego” finds an ancestor in the mental structure Kant called the “empirical unity of apperception.” I left out of consideration an important structure of our mental life: that “part” or aspect of the ego Freud calls the “superego,” which he explicitly relates to Kant’s “categorical imperative” of morality. In this fourth Lecture, I continue the work begun in Lecture 1 and consider the connections between those two notions (Freud’s “superego” and Kant’s “categorical imperative”).

In addition, I introduce a notion which is connected, in Freud’s account, to that of “superego” but plays a distinctive role in Freud’s genealogy of our moral attitudes: the concept of the “ego-ideal.” I examine the role of ideals in Freud’s view of morality as compared to Kant’s. We encounter here a new dimension of what I have called Freud’s “naturalization” of the structures of mental life he found in Kant.

I argue that Bernard Williams’s diagnosis of what he called the “morality system” is close to Freud’s diagnosis in both its positive and its negative aspects. I argue that both Williams’s and Freud’s diagnoses are eerily relevant for today’s moral quandaries.

In conclusion, I argue that Freud’s references to Kant throughout his mature work should be taken seriously. They should be taken seriously as a resource for understanding Freud’s thinking. But they should also be taken seriously by anyone sympathetic to Kant’s

transcendental approach to the mind but unpersuaded by Kant’s appeal to a purely intelligible world as the metaphysical ground for the structures of mental life he argues are necessary conditions for theoretical cognition, on the one hand; and moral responsibility, on the other. If we look for a naturalistic metaphysics of the mind as an alternative to the supernaturalistic metaphysics Kant offers as a ground for our a priori normative capacities, we could do worse than to take Freud’s metapsychology as a starting point of inquiry.

Suggested readings for Lecture 4:

Freud. The Ego and the Id. Sections 4, 5, 6.

Longuenesse. I, Me, Mine, Chapter 8.

Longuenesse. The First Person in Cognition and Morality. Chapter 2.

Williams, Bernard. Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy, Chapter 10: “Morality, the Peculiar Institution.” Fontana 1985, p.174–96.

György Geréby, Central European University, delivered the Isaiah Berlin Lectures at 5pm on the following days, in the Lecture Room at the Radcliffe Humanities Building.

Political Theology: a risky Subject in History

17 Jan: ‘Alexander's legacy. The Hellenistic justification of monarchy’

24 Jan: ‘Theocracy and the Kingdom of God. Biblical and early Christian polities’

31 Jan: ‘Christianity for and against the empire. Eusebius or Augustine?’

7 Feb: ‘“No church without an emperor.” The Byzantine symphony’

14 Feb: ‘Two swords and two luminaries. The conflict in the Latin West’

Professor Michael Friedman (Stanford University)

'The Idea of a Scientific Philosophy from Kant to Kuhn and Beyond'

Professor Michael Friedman (Frederick P. Rehmus Family Professor of Humanities, Stanford University) delivered the Isaiah Berlin Lectures on Wednesdays of weeks 4-8 of Michaelmas Term at 5 pm, in the T S Eliot Lecture Theatre, Merton College, Oxford OX1 4JD.

Abstract

These five lectures trace out a path through philosophical attempts to appropriate developments in contemporaneous science on behalf of an evolving conception of “scientific” philosophy from Kant, through the revision of Kant in the Naturphilosophie of Schelling and Hegel, to the neo-Kantian reaction to Naturphilosophie initiated by Hermann von Helmholtz, through the evolution of what came to be called history and philosophy of science as developed in the neo-Kantianism of Ernst Cassirer and (yes) Thomas Kuhn, and, finally, to my own attempt to develop a post-Kuhnian approach to the history and philosophy of science in light of these developments. The hope is to end up with a generalized and historicized version of the original Kantian conception of the relationship between science and philosophy that does full justice to the intervening radical changes having taken place in both, while still preserving a conception of trans-historical (but not ahistorical) scientific rationality in the Kantian tradition.

Details

Lecture 1 - 'Kant’s System of Nature and Freedom: Theoretical Science and the Demands of Morality' [Slides] [Lecture]

Reading: Kant's Construction of Nature [PDF]

Lecture 2 - 'The Challenge of Naturphilosophie: Kant, Schelling, and Hegel’ [Slides] [Lecture] [Quotes]

Reading: Space and Geometry in the B Deduction [PDF]

Lecture 3 - 'Nineteenth Century Scientific Philosophy from Helmholtz to Einstein' [Slides] [Lecture] [Quotes]

Reading: Helmholtz's Zeichentheorie and Schlick's Allgemeine Erkenntnislehre[PDF] Geometry, Construction, and Intuition in Kant and His Successors [ PDF]

Lecture 4 - 'Ernst Cassirer and Thomas Kuhn: The Neo-Kantian Tradition in History and Philosophy of Science' [Slides] [Lecture] [Quotes]

Reading: Kuhn, 1990 PSA Presidential Address [PDF] Friedman, Kuhn and Philosophy (2012) [PDF] Extending the Dynamics of Reason (2011) [PDF]

Lecture 5 - 'A Legacy of Kant in History and Philosophy of Science' [Slides] [Lecture] [Quotes]

Reading: Stein, On the Notion of Field in Newton, Maxwell, and Beyond (1970) [PDF], Yes, but . . .: Some Skeptical Reflections on Realism and Anti-realism (1989) [PDF]; Smith, The Methodology of the Principia (2002) [PDF], How Newton's Principia Changed Physics (2012) [PDF], Friedman, The Prolegomena and Natural Science (2012) [PDF]; Kennefick, Testing Relativity from the 1919 Eclipse (2009) [PDF]

Professor Robert Pasnau (University of Colorado)

'After Certainty: A History of our Epistemic Ideals and Illusions'

Professor Robert Pasnau (University of Colorado) delivered the Isaiah Berlin Lectures on Tuesdays of weeks 3-8 of Trinity Term at 5 pm on the following days, in the Lecture Room at the Faculty of Philosophy, Radcliffe Humanities Building (Woodstock Road, Oxford OX2 6GG).

Lecture 1 (13th May) - The Ideal

No area of philosophy is more disconnected from its past than epistemology. It is, indeed, only recently that epistemology has been recognized as a distinct field within philosophy. Rather than seek a precise analysis of anything in the vicinity of what we call “knowledge,” philosophers have historically been much more interested in articulating an idealized epistemology: an account of what it would be to have an ideal cognitive grasp of some part of reality, an ideal calibrated against what is possible for beings such as us, in a world such as this. For most of philosophy’s early history, this ideal was understood in terms of Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics, as the quest for demonstrative certainty grounded in the essences of things. But when that theory of essence comes into doubt in the seventeenth century, new conceptions of the epistemic ideal likewise arise, and a distinction emerges between the concept of knowledge and the concept of science.

Lecture 2 (20th May) - Certainty and Doubt

From antiquity through the Middle Ages and, most prominently of all, in Descartes, philosophers have pursued the epistemic ideal of certainty. It is not – as is so often said – that they took knowledge to require certainty, but rather that they regarded certainty as a crucial part of the epistemic ideal to which human beings should aspire. But beginning in the later Middle Ages, and even more in the seventeenth century, widespread doubts arose over whether certainty should be regarded as a part of the epistemic ideal achievable by us. Accordingly, in place of certainty, philosophers began to focus on probability, and began to articulate a new ideal: that we proportion our beliefs to the evidence. Out of this arises the concept of knowledge in something like our modern sense.

Lecture 3 (27th May) - The Sensory Domain

Pre-philosophically, it is often supposed that the cognitive ideal for beings such as us is to perceive a thing ourselves, directly. Philosophy from the beginning has directed much of its energies against this sort of naïve faith in sensation. Yet, even so, there has long been an abiding conviction among philosophers that there must be some domain where the senses get things right. Among Aristotelians, it was said to be the proper sensible qualities of things – color, sound, odor, flavor, heat – where the senses could be trusted not to err. In the seventeenth century, this doctrine was turned on its head, and those qualities now became the place where the senses most thoroughly lead us astray. At this point it becomes the so-called primary qualities – shape, size, motion – that the senses are best suited to perceive. Yet soon enough doubts arise even here, and philosophers begin to take recourse in the idea that what we perceive of the world are mere powers of bodies, powers that we can describe only as the things that cause us to have sensation. The character of the world itself begins to look quite inaccessible to sensory perception.

Lecture 4 (3rd June) - Illusions and Ideas

In place of a privileged access to the external world, seventeenth-century authors famously took the immediate objects of perception to be our own ideas. Although much attention has been given to the consequences of this doctrine, little has been said about its origins. There is a puzzle, in particular, about why philosophers began to talk this way, whereas for virtually the entire prior history of philosophy it was regarded as manifestly absurd to treat the objects of perception as inner sensory states. After canvassing and rejecting various alternative suggestions about what changed in the seventeenth century, I argue that what makes the difference is the increasing conviction that there are no suitable external objects for perception. So, if we see anything at all, the best candidates are not features of the external world, but features of our own mind.

Lecture 5 (10th June) - The Privileged Now

The final refuge of epistemic privilege – the one domain where our cognitive situation can seem to be at all ideal – might seem to be the self. Yet our privileged grasp of the self turns out to be a privileged grasp of the self right now – once it slips into the past, the privilege looks to disappear. So inasmuch as we seek to achieve the ideal, we need to consider just how many thoughts we can grasp all at once. Although such questions are not terribly familiar today, there is a long historical debate over the importance of grasping a whole argument all at once. In Descartes, in fact, such a possibility turns out to be critical to the method of the Meditations. Ultimately, however, there is reason to doubt whether we should privilege the present self in the way many philosophers have historically supposed.

Lecture 6 (17th June) - Skepticism and Hope

If our epistemic condition is sufficiently non-ideal, then the consequence may seem to be skepticism. Of course, if there is an all-powerful deity, then just as that being might deceive, so such a being might protect us from deception. But there is reason to wonder whether even an all-powerful deity could itself be completely confident of having knowledge. For even supposing that such a being cannot, by definition, be deceived, still there is a question of how can such a being know that it is such a being. This raises a more general question about whether the gap between how things seem and how they are is more than just an unfortunate feature of the human condition. Perhaps it is a logical feature of cognition in general that no evidence can ultimately be decisive in establishing any conclusion. If this were so, then the only alternative to skeptical suspension of belief might be an attitude of faith. Or, instead of faith, we might choose merely to hope, and so believe without pretending to have faith.

Professor Kenneth Winkler (Yale)

‘A New World’ – Philosophical Idealism in America'

Professor Kenneth Winkler is currently a Professor in the Faculty of Philosophy at Yale. His research interests include Early Modern Philosophy, Metaphysics, and American Philosophy. He will deliver the Isaiah Berlin Lectures on Tuesdays of weeks 1-6 at 5 pm on the following days at the Gulbenkian Theatre, St Cross Building, Manor Road.

Please note that the venue for the remaining Isaiah Berlin Lectures has changed. The lectures in weeks 3 to 5 will take place in the MBI Al Jaber Building, Corpus Christi College. The week 6 lecture will take place in the Fraenkel Room, Corpus Christi College.

Abstract

I've taken the title for my lectures from a letter by Samuel Johnson: not the Samuel Johnson, but the American Samuel Johnson. The Samuel Johnson responded to Berkeley's idealism with impatient physicality: he kicked a large stone and rebounded from it. The response of the American Samuel Johnson, who was writing to Berkeley himself, was appreciative wonderment, culminating in a plea:

You will forgive the confusedness of my thoughts and not wonder at my writing like a man something bewildered, since I am, as it were, got into a new world amazed at everything about me. These ideas of ours, what are they?

The metaphor of entry into a new world, or of a sojourn into new and wilder country, was one that Berkeley had already made his own. He promised readers of his Three Dialogues a "Return to the simple Dictates of Nature," but it would come, he said, only after a circuit through "the wild Mazes of Philosophy." In the end, he assured them, it would not be unpleasant. "It is like coming home from a long Voyage: a Man reflects with Pleasure on the many Difficulties and Perplexities he has passed through, sets his Heart at ease, and enjoys himself with more Satisfaction for the future." Time spent in a new world, he thought, would make us more comfortable and secure in our possession of the old.

My lectures will be a circuit through two "new worlds": the new world-system that bewildered Johnson, and the new world—the America—in which he lived. I'll be discussing writers who receive little attention from present-day philosophers, even in America: Jonathan Edwards (in Lectures I and II); Ralph Waldo Emerson (in Lecture III); Henry David Thoreau (in Lecture IV); Josiah Royce (in Lecture V); and the "Boston Personalists" (in Lecture VI, which will culminate with Martin Luther King). William James once described the study of literature as "an appreciative chronicle of human master-strokes," and bringing neglected good things to the attention of my listeners is certainly one of the items on my agenda. I'm also eager to combat two misimpressions: that the history of American philosophy is the history of pragmatism (though as I'll try to show, American idealists generally aspired to be practical); and that American idealism rests, as George Santayana claimed, on the "conceited notion that man, or human reason, or the human distinction between good and evil, is the centre and pivot of the universe." Despite the antique and implausible character of some of the arguments for idealism that I'll be examining, and the apparent absence of argument in many of the texts in which idealism is most compellingly asserted or intimated, the thought that the inward has some sort of priority over the outward, and that in our inwardness we make contact with a world less fugitive and more valuable than the world of sense, is not an easy one to shake. It is worth inquiring how successful a certain tradition was in bringing clarity to this thought, and in making it defensible and practical.

Details

Lecture 1 (17th Jan): Jonathan Edwards's early proofs of immaterialism [Handout] [Text]

Lecture 2 (24th Jan): Edwards and continuous creation [Handout] [Text]

Lecture 3 (31st Jan): Ralph Waldo Emerson's Nature [Handout] [Text]

Lecture 4 (7th Feb): Henry David Thoreau [Handout] [Text]

Lecture 5 (14th Feb): Josiah Royce and the argument from error [Handout] [Text]

Lecture 6 (21st Feb): Personalism, from Bowne and Howison to Martin Luther King [Handout] [Text]

Professor Michael Rosen (Harvard)

'History and Freedom in German Idealism'

Professor Michael Rosen, Professor in the Department of Government at Harvard University and this year’s Isaiah Berlin Visiting Professor in the History of Ideas, will give a series of six Isaiah Berlin Lectures this term, on Tuesdays of weeks 1 – 6, at 5pm in the Examination Schools. The first lecture will be followed by a short drinks reception to be held in Corpus Christi College (Rainolds Room).

Abstract

What exactly is the “history of ideas” a history of and what is its value? How does it relate to philosophy? Is it simply a backdrop to philosophical argument or can history make a substantive contribution to philosophical understanding? In the first two of these lectures I will offer answers to these questions and develop a perspective from which we can see the history of Western philosophy as a varying series of responses to some general questions of great depth and difficulty – in this case, the problem of theodicy and the question of the nature of value as we find it posed in Plato’s Euthyphro.

I shall use these two problems to frame an interpretation of an absolutely central feature of German Idealism: the account of freedom that we find in Kant and its continuation and transformation in the later German Idealists (in particular, Hegel). On the one hand, I shall argue, the Kantian conception of freedom is part of a network of connected concepts such as duty, responsibility, law, justice and desert. Together they sustain a picture of agency according to which the free agent must use her freedom in such a way as to merit the approval of a just God. God does not make moral action valuable by approving or rewarding it, but our world can be seen as a good world because in it such intrinsically valuable action is possible.

The puzzle of later German Idealism is that, while it retains and builds upon the Kantian conception of freedom as autonomous self-determination, it rejects the conception of morality and agency that is associated with it. My claim is that, to understand it, we should take seriously the idea that, for German Idealism, “die Weltgeschichte ist das Weltgericht” (the history of the world is the Last Judgement) – that history takes the place of God. This entails a radical re-working of the ideas of morality and justice that is, I believe, of great interest and surprising relevance today.

Details

Lecture 1 (19 Jan): “How (and to what end) should one study the history of ideas?” [Handout]

Lecture 2 (26 Jan): “The Idealist theory of history defended (sort of)” [Handout]

Lecture 3 (2 February): “Kant’s anti-determinism” [Handout]

Lecture 4 (9 February): “Freedom without arbitrariness” [Handout]

Lecture 5 (16 February): “Die Weltgeschichte ist das Weltgericht” [Handout]

Lecture 6 (23 February): “Geist and the individual” [Handout]

*** Michael Rosen will be holding informal office hours after each lecture. On Wednesdays they will take place from 1.45 - 2.45pm in the Fraenkel Room in Corpus Christi College. All are welcome to drop by.

He may also be contacted by email at michael[DOT]rosen[AT]philosophy[DOT]ox[DOT]ac[DOT]uk ***

Professor Jonathan Israel (Princeton)

'Enlightenment Ideas and the Making of Modernity (1670-1800)'

Lecture 1 (24 January): Progress; or, the Enlightenment's Two Ways of Improving the World

Lecture 2 (31 January): Democracy or Social Hierarchy? The Political Rift

Lecture 4 (14 February): The Problem of Equality and Inequality; or, the Rise of Economics.

Lecture 5 (21 February): The Enlightenment's Critique of War and the Quest for 'Perpetual Peace'

Lecture 6 (28 February): Two Kinds of Moral Philosophy in Conflict

Lecture 7 (6 March): Locke and Voltaire versus Spinoza and Diderot; or, the Enlightenment's Basic Dichotomy as a War of Philosophies

Lectures to take place in the Examination Schools, High Street at 5pm each Thursday as listed above.

Professor Allen Wood (Stanford)

'Kantian Ethics'

Abstract

The ethical theory presented in Immanuel Kant’s writings on moral philosophy continues to exert great influence, but also to be a focus of much controversy. These six lectures attempt to present sympathetically Kant’s central thoughts about moral philosophy in a way that challenges some prevailing ideas both about what Kant thought and about how moral philosophy should be done. I sketch Kant’s conception of the aims and structure of ethical theory, and stress the importance to Kantian ethics of Kant’s empirical theory of human nature. In examining Kant’s formulation of the moral law, I attempt to correct the traditional overemphasis on his first and most provisional formula, and to put all Kant's formulas in their proper place within the complete system of formulations which was the object of Kant’s search for the supreme principle of morality. The fundamental value in Kantian ethics is the worth of rational nature as an end in itself and the dignity of autonomous personality. I sympathetically present Kant’s argument for this value, and then reflect on its proper extension and its implications for some controversial ethical questions, such as the morality of abortion and the moral status of nonhuman animals. Kant’s ethical theory proper consists in the theory of duties that is based on the principle of morality. I will discuss Kant’s use of the concept of duty, the structure of his system of duties, and then defend the distinctive Kantian conception of a duty to oneself. The last two lectures will talk about three ethical topics on which Kant’s position has often been regarded as positively scandalous: sexual morality, the prohibition on lying, and the retributive theory of punishment. My aim will be to determine how far a consistent Kantian should agree with Kant’s own opinions on these subjects, and to demonstrate the continuing value and relevance of Kant’s reflections on all three topics, whether or not in the end we should agree with his conclusions about them.

Details

There were six lectures in weeks one to six of Michaelmas Term 2005, as follows:

Lecture 1 (11 October): What is Kantian Ethics?

Lecture 2 (18 October): Formulations of the Moral Law

Lecture 3 (25 October): Humanity, Personality and Dignity

Lecture 4 (1 November): Duties to oneself

Lecture 5 (8 November): Sex, Lies (without the videotape)

Lecture 6 (15 November): Punishment and Retribution

The lectures took place on Tuesdays at 5pm in the Examination Schools (East School).

Professor Daniel Garber (Princeton)

'Enchanting the World: How Leibniz Became an Idealist'

Abstract

In these lectures, I would like to present a way of understanding Leibniz's development, from a heterodox Hobbesian in his mid-twenties to a full-blown idealist by the end of his career. I want to undermine the assumption that the idealism that characterizes his later years, the monadology that forms the core of the text-book Leibnizian philosophy is all there is to Leibniz's philosophical thought. Along the way, I want to introduce into discussion what amounts to a new character in the history of philosophy, a rich thinker with a complex reaction to the Cartesian synthesis of the late seventeenth century, a view that brings together physics, metaphysics, logic and theology in interesting and surprising ways.

Details

How to do things with texts. And why bother?

Leibniz the Radical Reactionary: First Steps

The Soul in the Machine: Transforming the Cartesian World (I)

The Soul in the Machine: Transforming the Cartesian World (II)

Oh, dear, what can the matter be?

The Enchanted World and Beyond